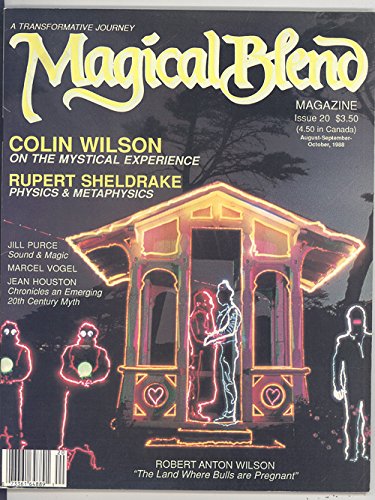

The Land Where Bulls Are Pregnant

by Robert Anton Wilson

from Magical Blend, Issue 20, Aug-Sept-Oct 1988

There are four clocks atop the City Hall tower in Cork, facing the four quarters, and since Cork is in Ireland the four clocks always show four different times, none of which is ever correct. People in Cork refer to them as “the Four Liars.”

After six years in the Alternative Reality of Erin, I find the Four Liars to be the single best symbol, or synechdoche, to summarize all that I have learned about the Irish people and the strange, eerie charm of Gaelic culture. Do not understand me too quickly. It is not that “the Irish” as a collective or “ethnic” group lack some genetic endowment connected with mechanical ability, or do not know how to repair a clock. Not at all: they build excellent computers-my Irish-built Macintosh Plus is a superb instrument-and most of the computer companies are in Cork where the Four Liars continue to tell you the wrong time four different ways if you walk all the way around the City Hall.

Irish Time simply is not identical with ordinary or linear time. My wife Arlen and I never found two clocks in the whole country that agreed. Once, when I was still new to Irish Time, I returned to Ireland from the continent and set my quartz watch to agree with the time on the official radio station, RTE; the next day the watch and the radio station disagreed by four minutes. I wondered if something was wrong with my watch and re-set it; the next day it disagreed with the radio by six minutes…Then I discovered the radio time and the television time also disagreed, even though Irish radio and TV come out of two facilities in the same building complex in Donnybrook. When it is 6:05 on Irish radio, it is often 6:10 on Irish TV.

James Joyce once pointed out that there are only three world-class philosophers of Celtic origin-Scotus Erigena, Bishop Berkeley, and Henri Bergson (who was a Breton Celt)-and all three of them denied the reality of time. Joyce indeed seemed to think there was some genetic basis for the Celtic rejection of the normal time-sense of the rest of the Occident. I’m not sure of that. Others, including some Irish sociologists, claim that the Irish time-sense is similar to that of other colonial or post colonial people and represents a form of unconscious sabotage of the colonizer’s reality-grid.

Whether the basis be genetic or sociological, there is no doubt that Irish Time is more relative than even Einsteinian time and seems infinitely flexible in all directions. For instance, if you hire a plumber and he tells you he will come “Tuesday week,” that literally means one week from Tuesday but actually he’ll come when he feels like it. “Tuesday fortnight,” however, is even more daunting: it literally means two weeks from Tuesday but actually it indicates that the job sounds hard and the plumber will probably never come at all. Most events in Irish Time occur in the occult interval between temporarily uncertain Tuesday week” and for-ever uncertain “Tuesday fortnight,” which I think is the time it takes Schrödinger’s cat to jump from one eigenstate to another.

If you suspect that the wobbly time-sense of Eire can be explained entirely as a manifestation of the calculated procrastination of colonial peoples, you are probably missing the complexity of the Gaelic mindset. One story tells of the two clocks in Padraic Pearse Station, Dublin, which, of course, being Irish clocks always disagree. An Englishman, this story claims, once commented loudly and angrily on how “typically Irish“ it was to have two clocks in a train station that gave different times. “Ah, sure,” a Dublin man replied, “if they agreed, one of them would be superfluous.”

The logic there might not be Aristotelian but it has its own internal consistency, like a Monty Python routine. One encounters such ratiocination frequently on the Emerald Isle. The day I arrived (16 June 1982: Bloomsday), I heard some interviews on radio, which were part of what I later learned was an oral history of modern Ireland being compiled by RTE-Radio Telefis hEirann, the government radio-TV monopoly. These interviews concerned the pookah, a six-foot-tall white rabbit often reported in County Kerry-although one pookah, named Harvey, wandered as far as Broadway and became the hero of a famous play. Legends of the pookah probably date back to the Stone Age, and some etymologists even think “pookah” and “god” come from the same pre-Indo-European root, which also gave us Shakespeare’s Puck (pronounced “pook” in Elizabethan times), the Russian bog (god) and that familiar childhood demon, the bogie or boogie.

One Kerry farmer interviewed on this documentary was particularly knowledge-able about the pookah and had endless stories about men who had encountered him on their way home from the pub at night. (For some reason, the pookah seems to prefer to play his tricks on men returning from pubs, especially if they have had more than fourteen pints of Guinness. In the Broadway play, Harvey the pookah first encounters Elwood P. Dowd coming out of a bar.)

“Do you believe in the pookah yourself’?” the interviewer asked finally.

“That I do not,” said the farmer with exquisite Kerry logic, “and I doubt very much that he believes in me either.“

Most of the Irish insist that such reasoning is peculiarly native to Kerry. I doubt it, but there are countless Kerry legends that are cited as examples. In the time of the Troubles, it is claimed, an English landlord in Kerry was found dead of forty-seven pistol wounds and the jury pronounced it “the most aggravated case of suicide in our experience.” In another case, a Kerry jury allegedly ruled, “We find the defendant innocent, but he better not do it in this town again.” There is even a story claiming that one judge released a defendant with the words, “You have been found not guilty and may leave the court with no stigma on your name, except of course for being acquitted by a Kerry jury.“

Most of this, no doubt, is folklore-and Kerry stories are indeed most popular in Dublin. (They even say you can sink a sub-marine full of Kerry men by knocking on the door.) I’m told that in Kerry they tell similar stories about Dubliners. One yarn claims that a millionaire left all his money to build hospitals for the insane. The executors, it is said, built one hospital in Galway; and another in Limerick, and then put a roof over Dublin.

I could go on about such local Irish chauvinism at great length, but instead I would like to explore further into what baffled commentators call the Celtic Twilight. In Illuminates! I proposed that all oppressed people seek revenge against their oppressors by pretending to be even more “backward” than the propaganda line of the oppressor claims. Women used to do this, too, before Feminism: remember the dumb wife played by Gracie Allen and all the dumb blondes in old films?

Ireland was colonized before any part of Asia, Africa or the Americas-the first British invasion began on 23 August 1170—and British troops even today patrol six counties that arc called Northern Ireland and are still part of the British Empire.

Meanwhile, an Irish Bull is a kind of oxymoron, or sentence that contradicts itself. Some linguists love Irish Bulls so much they have made book-length collections of them. One of my favorites is the legendary Dubliner’s response to “Bad weather for this of year, is it not?” The reply was “Ah, faith, it isn’t this time of year at all.” Perhaps the all-time classic Bull was uttered by an Irish member of Parliament: “Children who are too young to walk or talk are running about the streets blaspheming their Maker.” Joyce’s Ulysses is full of Irish Bulls; a choice example is All Bergan’s reply when asked who made certain allegations: “I’m the alligator:”

One theory alleges that Irish Bulls result from thinking in Gaelic and trying to talk in English at the same time. Maybe; but I tend to agree, rather, with Anthony Burgess who argues in his RE:JOYCE that the English spoken in England and America has become increasingly “functional” in recent centuries, but Irish English retains the “ludic” qualities of earlier epochs.

On the other hand, an Irish Bull is like a surrealist painting: it jolts you out of your ordinary reality-tunnel and shows you a whole new landscape of possibility.

Ireland is the land where Bulls are pregnant.

But, listen now: during the 1840s Potato Famine, while two million of the Irish died, the English continued to enforce the Poaching Laws. Any Irishman who tried to feed himself or his family by hunting or fishing was hanged if caught, because the land and the rivers both were owned by English landlords.

I don’t think the English were worse than any other conquerors. Similar horror stories can be told about any land occupied by an imperialist power. But you do not understand Irish humor unless you understand the enormous human tragedy out of which that humor grew.

Oscar Wilde was more Irish than readers in America generally realize. It is very Hibernian, indeed, that his best-known (and funniest) play has a title that suggests it is about the importance of honesty or sincerity, but the play is actually about clandestine homosexuality and impersonators impersonating other impersonators…

Wilde also wrote a little-known essay, ‘The Reality of Masks,” which uses the drama as an example to demonstrate that illusions are often real and reality is often illusory. “The reality of metaphysics is the reality of masks” is the typically Wildean paradox on which the essay climaxes; and Yeats developed his poetic theories of Mask and Anti-Mask out of Wilde. This Yeatsian mystique of Mask, Anti-Mask, Self, Anti-Self, etc. helped make classic Japanese drama comprehensible to Westerners; but what would you expect? Yeats himself pointed out that “Ireland was part of Asia until the Battle of the Boyne.“ I often think it is still part of Asia.

But, again, the Celtic Reality-Labyrinth cannot be reduced to a formula. Most critics think Yeats’ Mask and Anti-Mask have only a poetic and metaphysical meaning. A look at the man’s life reverses that opinion. Yeats was not only a member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, the most high-voltage occult group then active in Europe, but also of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, which was hatching the conspiracy that birthed the bloody revolution of 1916. “How can you tell the dancer from the dance?” he once asked explicitly. How can you tell the Mask from the Anti-Mask?, his best poems all ask implicitly. In Ireland, you seldom can and eventually you stop trying.

Thus, in Flann O’Brien’s The Third Policeman – which I consider the greatest Irish novel since Finnegan’s Wake – the narrator reflects that while it is good if people know nothing about you, it is even better if they know several things which are not true. This could almost be called the first Axiom of Irish Sociology. Naturally – this should be no surprise, if you have followed me this far – Flann O’Brien himself did not exist. He was considered the funniest Irish novelist of his time, just as Myles na gCopaleen was considered the funniest newspaper columnist of the same years (the mid-1930s to mid-1’950s), but then Myles na gCopaleen never existed either. Both O’Brien and na gCopaleen Were inventions of Brian O’Nolan, a minor clerk in the government bureaucracy. (If Kafka had lived in Ireland, he would have been equally perplexed but more amusing about it.)

When Time magazine discovered O’Brien’s novels, or O’Nolan’s novels, they did an interview with him, in his normal space-time identity as O’Nolan. They printed every yarn he told them, including a marvelous fantasy about defeating Alekhine, the world champion, at chess. Evidently, Time did not fully understand Irish Facts. I doubt that anybody does understand Irish Facts, but Professor Hugh Kenner attempts to define Irish Facts in his study of recent Irish literature, A Colder Eye. Prof. Kenner gets quite metaphysical about the matter, and seems to regard Irish Facts as incomprehensible to the non-Irish, but I think an Irish Fact is simply, like a rubber inch or one of Dali’s melting clocks, an attempt to create a realm of communication wherein six-foot-tall white rabbits can survive despite all “English” or Rational attempts to banish them.

For instance, if you ever studied Modern Literature at all, you know the story about

what Joyce did on Yeats’ 40th birthday. He went to the hotel where Yeats was staying and said, “I hear you’re 40 today.” Yeats allowed that such was the case. “Too bad,” Joyce replied. “That means you’re too old to be influenced by me.”

That is a typical Irish Fact. It is in many biographies of Joyce, most biographies of Yeats, standard histories of Irish Literature, etc. It got into all those sources because, as Prof. Kenner pointed out, most American researchers do not understand Irish Facts and assume they are similar to American Facts or English Facts or ordinary everyday Facts,

The source for this widely published story was Oliver St. John Gogarty, one of the greatest inventors of Irish Facts in this century (and the model for “Buck Mulligan” in Joyce’s Ulysses). The major flaw in this particular Gogarty invention is that when Yeats was 40, Joyce was living a thousand miles from Dublin in Trieste, Italy.

Nonetheless, an Irish Fact has its own beauty, even if it does not correspond to ordinary actuality. The more you understand the relationship between Yeats and Joyce, the more you realize that if Gogarty’s yarn never happened, it should have happened. It is not just Irish Bulls that are pregnant; Irish Facts are equally fertile.

Gogarty, incidentally, is the hero of one of the great stories of the Civil War. He was one of the senators who voted to accept the Treaty of 1922, which granted Ireland semi-independence from England, and the IRA set out to assassinate all the senators who had voted for that Treaty. They grabbed Gogarty at his home one night, took him to a car, and drove him to a lonely spot in the country for the execution.

“Am I expected to tip the driver?” Gogarty asked, or claims he asked.

Then, when the IRA was about to shoot him, he asked for permission to take a piss CO. Being Irish, they allowed him to go behind a bush. He kept going until he got to a river, swam to the other side, and escaped.

I don’t know whether that’s an Irish Fact or a normal Fact, but it was a story Gogarty loved to tell. Ezra Pound wrote a poem about it, too, `so now, like many things Gaelic, it is literature even if it is not actuality.

And Joyce, when asked for maybe the thousandth time why he was writing a book as “queer” as Finnegan’s Wake, replied “To keep the Ph.D. candidates busy for the next thousand years.” Was that another Irish Fact? Does it represent Joyce’s Mask or his Anti‑

Mask? His Self or his Anti-Self? And (to parody one of his famous parodies) if not, why not? You have to deal with such puzzles if you want to read Irish literature, and you even have to deal with them if you ask the time in Dublin.

There is a sea-walk at Sandycove, on the southern rim of Dublin Bay, that illustrates the sociological ramifications of Irish Time, Irish Logic, Irish Facts and the Hibernian imagination in general. This sea-walk is about ten feet below the street-walk, and gives one a more intimate view of the Bay and the birds and other flora and fauna that flourish there. Just as you come in sight of the James Joyce Tower-an unpopular building commemorating the man who may be Ireland’s greatest (or perhaps its only) Rationalist-the sea-walk gives you a Celtic Surprise, There is a brick wall in the middle of it, and you cannot walk further. You can try to climb the wall, if you feel athletic, or you can jump in the water and swim around It you don’t mind getting your clothes wet, or you can turn around and go back the way you came.

The sea-walk does not terminate, please understand; it continues on the other side of the brick wall. You really ought to go there someday to look at that brick wall, and then try to decide for yourself if there is a solution to the puzzle better than the three alternatives above-or if the wall is another Gaelic satire on the Rationalist’s faith that all things in the Universe are comprehensible.

Arlen probably has the right answer. She suggests the sea-walk was constructed before 1922-i.e. when all Ireland was still colonized-by Irish workers who were supervised by an English foreman. If so, I imagine they constructed the wall while he was watching but, as Holmes would say, not observing.

A similar explanation was offered to me by a student at Trinity to explain why the Dublin telephones are notoriously the worst in Europe (even worse than the French) but Irish country phones work quite well usually. The Dublin phone lines were installed during the British occupation. The country phone lines have been installed since Independence. See?

But the socio-psychology of Colonialism only carries one part of the way in grappling with Celtic Mysteries. For instance‑

Ireland has the highest schizophrenia rate in Europe, and 90 per cent of the schizophrenics live in the same two counties (Clare and Connemara), which suffered the greatest population loss during the Potato Famine of the 1840s. Many Irish writers had a special fondness for those counties – “A.E.” (George Russell), Liam 0′ Flaherty, W.B. Yeats and John Millington Synge, for instance-and found the people there especially “wise” and “mystical.” Did some genes mutate during the famine, or did the trauma of mass starvation send psychic terrors down through the generations to the present?

Bob Quinn, a native of Connemara, doubts both these theories. Quinn, a producer of films for RTE, claims the West Irish, especially in those two counties, are not basically Celtic but pre-Celtic. He thinks that what makes the West Irish seem “schizophrenic” to doctors and “mystical” to poets is that they are not really Europeans at all. (I find this fascinating because 25% of my ancestors come from that area…) In three one-hour films collectively and misleadingly titled “Atlantean,” Quinn preaches his doctrine using such evidence as:

Irish step-dancing resembles Spanish flamenco and the dancing of North African Berbers.

The journey from North Africa around the Celtic-speaking coast of Spain, up past Celtic France to West Ireland, is a trade route known to exist for several hundred years, and perhaps for millenniums.

West Irish music hasa different tonal scale than ordinary European music. Playing the tunes of Connemara to musicologists and asking them to identify the tunes, Quinn found most of them guessed “African” although a

few said “Asiatic.”

Type 0 blood is rare in Europe, but common in North Africa. It is also common in Clare and Connemara.

A Christian cross with the Arabic word BISM’ILLAH (“In the name of God…”) has been found in Kerry and carbon-dated at 900 AD.

Basically, itis Quinn’s thesis that the Irish as an ethnic group contain more African-Arabic and pre-Celtic genes and cultural traits than they realize. He wants the Irish to give up Celtic Pride they developed during their Revolutionary epoch and develop a sort of pre-Celtic Pride, you might say. He even claims the Celts never existed as a distinct ethnic group and “Kelltoi” was just a general label the Romans pinned on all tribes they met in Europe.

Only God and Bob Quinn know why he presented this theory using an English-speaking narrator for his three films and yet appears in them himself speaking only Gaelic, the language that has been associated with Celtic Pride since the Gaelic revival of the 1890s.

I mentioned earlier that the IRA once tried to assassinate every Senator who ratified the Treaty of 1922. One article that the IRA found unacceptable ordained that every member of the Irish Parliament, dail hEirann, had to take an oath of loyalty to the English king (or queen).

When de Valera left the IRA and entered the dall in 1927, he took the oath of loyalty. Or did he? They are still arguing about it, in Dublin. Dev ‘s followers spread the rumor that he carefully did not let his hand actually touch the Bible while taking the Oath, and ergo the Oath was null and void. (In any case, Dev was able to get that article of the Treaty abolished in 1937, ten years later.)

You see, Dev, like most Irish politicians (and intellectuals), had a Jesuit education, and the words “casuistry” and “equivocation” have been associated with Jesuits for so long that to say one had a Jesuit education is to say that one can prove two plus two equals five anytime there is a need to prove it, and also that one can quickly reconstruct the proof that two plus two equals four if one’s opponents try to argue that it equals five.

Irish Logic and Irish Facts and Irish Time and all the rest may not be entirely explicable in terms of the psychology of the colonized, or Celtic mysticism, or possible non-European genetic/cultural traces, etc. A lot of the extraterrestrial or at least extramundane quality of the Irish imagination may result from Jesuit education…

I once interviewed Sean MacBride, co-founder of Amnesty International, winner of the Lenin Peace Prize, the U.S. Medal of Justice, the Dag Hammarskjold Medal of Honor of the UN, and the Nobel Peace Prize. He probably did more to secure the release of political prisoners, all over the world, than any man of his time.

“Ireland is a third world country,” he told me.

Ireland is officially reckoned the second poorest country in the European Economic Community (only Portugal has more poverty), yet in public opinion polls the Irish always rate themselves as much happier than other Europeans. American tourists are always astounded that the Irish can be happy without being rich.

“It’s the gargle,” said Irish TV star Gay Byrne, trying to explain this. “The gargle” is Irish whiskey; Byrne meant the population is too drunk most of the time to notice how miserable they are. But Byrne is a Social Critic by profession and Social Critics hate to admit that anybody is really happy.

An American friend who spent six months in Ireland once told me that the honesty of the Irish was the most striking thing about them. Indeed, coming from America, one’s first impression is that the Irish are less paranoid than Americans; only later do you realize that they trust you because they trust one another and have little experience with con-artists and swindlers.

“You know what it is?” my friend asked me rhetorically. “They still believe in Hell. If you leave your wallet in a pub, the waiter will chase you down the street to give it back, because he thinks he’ll go to Hell otherwise.”

Yet Liam O’Flaherty’s Autobiography begins with the blunt warning sentence “All men are born liars.” (Empedocles the Cretan, who said Cretans always lie, must have been part Irish, I guess…)

Ireland is 95% Catholic and every August the natives of Kerry have a holiday in which a goat is crowned and Dionysian revelry follows. The Church has fulminated and fretted for centuries, but the good Catholics of Kerry insist on remaining good pagans as well. What else could you expect in a place where six-foot rabbits still roam the night?

It was in Kerry, also, in 1986, that literally thousands of people saw a statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary move and make gestures, over a period of three months. To show how contagious such things are, foreign tourists saw the “miracle” as often as natives, and June Levine, a Jewish Feminist from Dublin, also saw it.

Some people, including agnostic Conor Cruise O’Brien and a cameraman from RTE, saw strange lights in the sky when the Lady was performing. “UFOs?” you may ask. Search me. The Kerry people probably thought they were seeing fairies.

Incidentally, the BVM in Kerry-in a town, by the way, which had the wonderful name, Ballinspittle-finally stopped moving after October 31, 1986. Two Protestants from Dublin drove down to Kerry that night-Halloween, to Americans; Samhain, to the Celts-and bashed Her head in with hammers, while ranting against “Idolatry” to the Catholic witnesses.

The joke in Dublin the next day was “Why didn’t She duck?” Dublin has more atheists per square foot than Moscow, I think. They were all educated by the Jesuits and express themselves with superb eloquence. After Archbishop McNamara issued some dogmatic thoughts on “God’s plan for family life,” one of these Jesuit Atheists wrote a letter to the press imploring His Eminence to ex-plain, in detail, how, and with what degree of metaphor, a timeless being can be said to have plans.

Up until the 19th century, nobody but an Irishman would seriously argue against the proposition that, in algebra, pq = qp, which means that if you multiply two quantifies the result is the same whether you multiply the first by the second or the second by the fast.

Even those of you who hate mathematics remember that much algebra, I’m sure. 3 x 5 = 5 x 3. If you buy 3 oranges for 5 cents each, it will cost you as much as buying 5 apples for 3 cents each, because 3 x 5 always equals the same as 5 x 3, namely 15 cents. That’s what the general expression pq = qp means. Right? It’s only common sense.

Naturally, an Irishman finally challenged that. His name was William Rowan Hamilton and he made so many original contributions to math that some consider him on a level with Euclid, Gauss or Descartes. His most astounding and Celtic production, however, was what is called non-communicative algebra, or Hamiltonian algebra, and it is the system in which pq does not equal qp.

The most startling recent finding in quantum math, as everyone has heard by now, is Bell’s Theorem, which proves that quantum systems once in contact remain correlated no matter how far a part in space or time they may move. Prof. Nick Herbert explains this in the homely language it deserves. “There is no difference between anything,” Herbert says. “Here is there.”

The inventor of Bell’s Theorem was an-other Irishman, John S. Bell, born in Belfast

Irish Logic may have survived, evolutionarily speaking, because even the Western half of the human race needs alternatives to orthodox European (Aristotelian) logic. Until we discovered Buddhism and Taoism in this century, we needed the Irish to remind us that clock time is not living time and a bull may be pregnant Maybe that’s why the Irish survived, despite all the Brits did to eliminate them.

[submiteed to rawilsonfans by RMJon23]