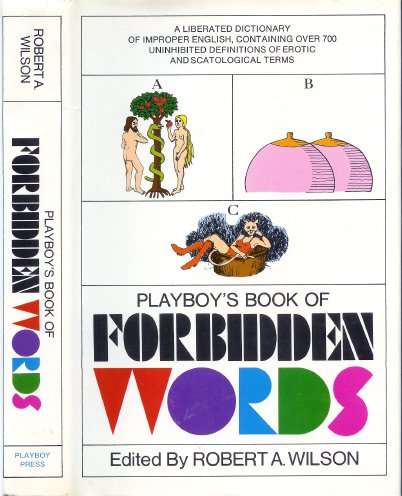

Introduction to Playboy’s Book of Forbidden Words, 1972

“Zounds, I was never so bethump’d by words. . .” – SHAKESPEARE, King John

Modern American English is a language with numerous levels, like a skyscraper. The bottom floors are words like table, chair, door and window, known to everybody; the upper stories are words like synergyand cantharis and Hilbert space and transubstantiation – esoterics which you can easily look up in an ordinary dictionary. But there is a basement, rented out to various shady and suspicious characters whokeep screaming hysterically or muttering suggestively in a language which is most definitely not to be found in standard dictionaries. Some of this underground vocabulary, such as luck and cunt, is known to everybody, despite society’s official rejection, but other terms, such as muff-diver and beard-splitter and vacuum cleaner, are known only in certain parts of the country and are totally obscure to even the best-educated foreigners. And even those subterranean words that all of us recognize ate still mysterious; if we wonder about their history or antecedents, or whether they are related to certain similar-looking “respectable” words, or how and why they have been purged from polite speech and school dictionaries, or any of a dozen similar questions, we find it hard to discover the answers. The books which areSupposed to contain such information usually are, in this area, strangely silent-superstitiously silent.

Modern American English is a language with numerous levels, like a skyscraper. The bottom floors are words like table, chair, door and window, known to everybody; the upper stories are words like synergyand cantharis and Hilbert space and transubstantiation – esoterics which you can easily look up in an ordinary dictionary. But there is a basement, rented out to various shady and suspicious characters whokeep screaming hysterically or muttering suggestively in a language which is most definitely not to be found in standard dictionaries. Some of this underground vocabulary, such as luck and cunt, is known to everybody, despite society’s official rejection, but other terms, such as muff-diver and beard-splitter and vacuum cleaner, are known only in certain parts of the country and are totally obscure to even the best-educated foreigners. And even those subterranean words that all of us recognize ate still mysterious; if we wonder about their history or antecedents, or whether they are related to certain similar-looking “respectable” words, or how and why they have been purged from polite speech and school dictionaries, or any of a dozen similar questions, we find it hard to discover the answers. The books which areSupposed to contain such information usually are, in this area, strangely silent-superstitiously silent.

This book attempts to answer such questions; in a leisurely and detailed manner and without a lot of academic technicalities. It is written for the general reader. The definitions are alphabetically arranged, and there are many cross-references.

What has happened among the youth in this country in the past decade-the first wave of “the Greening of America,” pot and LSD, women’s liberation and many other wild and unforeseen events-has badly shaken the old sex-is-dirty philosophy, replacing it with the view that sex is beautiful. Significantly, a book on explicit sexual terms can now be written, published and accepted, without the elaborate circumlocutions and euphemisms which the Kronhausens had to use in their book, Pornography and the Law, in 1959. That book was a work of social science that, in a sense, was written in code. From the vantage point of 1972, this is astonishing. Writing about the effect of the word luck on the human mind, these two scientists could not use the word luck. It was as if an engineer had to publish his analysis of our kilowatt capacity without ever mentioning volts, amperes or ohms.

Those days are gone, hopefully forever, but many people still wish that a book such as this one could not be published; and if it cannot be suppressed in the nation as a whole, they will try to ban it in their own communities. I have a certain sympathy for these people. A cynical old joke says that “a dirty mind is a joy forever,” but actually it is quite dreary; such as an excessively puritanical, sexually repressed mind is capable literally of driving a man crazy.

The new freedom, however, did not arrive in a decade and it did not arrive without suffering and conflict. James Joyce, for instance, endured decades of poverty because his masterpiece, Ulysses, could not be copyrighted in the United States due to a detail in the censorship laws of that period. Pirated editions sold widely, but the pirates received the profits; Joyce got not one penny from 1917 until the book was declared innocent of obscenity in 1934. D.H. Lawrence became depressive and somewhat paranoid, according to his friends, due to the censorship problems of Lady Chatterley’s Lover and some of hispaintings, and this may have hastened his premature death. And Frank Harris not only had his books alternately banned and bowdlerized, but was castigated as a monster and degenerate, for frankly acknowledging behavior which Kinsey much later was to describe as statistically normal. (Even earlier, Anthony Comstock, champion of censorship in the latter 19th Century, used to boast quite happily about the number of publishers he had driven to suicide.)

Henry Miller, a much tougher individual than Joyce or Lawrence, doesn’t seem to have suffered as much, but it remains a scandal that this pioneer, certainly one of the five or ten major Novelists of our century, could not have his works published in his own country until he was quite an old man. And Lenny Bruce, s0cial satirist of the night-club beat, seemed even tougher than Miller at first, but after nine obscenity convictions, and prison terms running into decades, he was reduced to pauperage and died of a heroin overdose that might have been suicide. Ironically, all his convictions have been overthrown by higher courts and, legally, he is now adjudged totally innocent of the “crime” of “obscenity.” Nevertheless, he died.

The list of important contemporary writers who have had censorship problems in one part of this country or another reads like an honor roll of the great and near-great: John Steinbeck, James T. Farrell, ErskineCaldwell, William Faulkner, Ernest Hemingway, William S. Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, John O’Hara, J. D. Salinger-and virtually everybody who has ever received a Nobel or Pulitzer prize. The folly reached some sort of climax in 1934 when reproductions of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel frescoes were banned from the U. S. mails. These frescoes, be it noted, had looked down for 500 years on the coronations of popes!

The principal input in the human communication matrix is Words, and every word beyond simple ejaculations such as oh wow or ouch was originally a poetic metaphor. Even to be goes back to an Indo-European root meaning to be lost in the woods. To have means to take hold of with the hand, and to want signifies to be vacant or empty. These “buried poems” in every word we speak are chains of command as well as of communications. In the technical language of semantics, we are governed as much by the connotations (emotional overtones) of words as we are by their denotations (the objects to which they refer). To quote an old example, we would rather eat “a tender, juicy piece of prime steak” than “a hunk of dead, castrated bull.”

“What is hardest of all?” Goethe once asked, and replied, “That which seems easiest of all: to see with your eyes that which is before your eyes.” Unfortunately, we do not see what is before our eyes; we see what we are programmed to see, and in human beings the chief programming device is language. We see what our language teaches us to see. In short, “dirty minds” are created by “dirty words.”

One of the greatest symbols in the history of mankind is the Greek centaur. We are all psychological centaurs-half animal (according to our own definition of animality) and half human (again, according to our own glamorous and self-serving definition of humanity). We are so at odds with the animal half of ourselves that we even try to ignore or hide the simple fact that we reproduce in the same manner as other mammals. Confronted with sex, all of us are inclined to feel something of that sense of un pleasant self-revelation that occurs when, looking through the bars of the monkey cage, we recognize ourselves on the other side. The attempt to evade the problem entirely by ruling sex out of our lives, however, is foredoomed to failure. One is reminded of the old Hindu story about the man who was promised a million rupees if he could avoid thinking of a rhinoceros for a whole day. Naturally, once the offer was made, he could think of nothing but rhinos-big rhinos, little rhinos, rhinos alone and rhinos in twos and threes, rhinos dancing and rhinos running, rhinos flying, even rhinos in impossible acrobatic positions.

The same thing happens to the antisexual prude, on a grander scale, because sex is more intrinsic to our mental processes than rhinoceri are. Such sex-haters think about sex more than the rest of us-big sex, little sex, sex alone and sex in twos and threes, sex dancing and sex running, sex flying, even sex in impossible acrobatic positions.

If anything stands out about Anglo-American attitudes toward native sexual terms, it is that our laws and customs were created by people who seem to have been seriously worried that the word luck could make their teen-age daughters pregnant, and that other words could turn whole populations into rapists, “sex maniacs” and depleted, hopelessly drooling, erotic imbeciles only fit for the ferbleminded ward of the state hospital.

Every society has its forbidden words, but they are usually connected with death or the deities. The taboos surrounding them are, within the belief system of the tribe, rational. Thus, the ancient Jews and Romans could not speak the names of certain gods aloud, but this was motivated by courtesy and awe; it was felt that the gods did not like to be pestered except on important business. It was also feared that enemies, learning a god’s name, could compel him to obey them. Similarly, according to Frazer’s Golden Bough, Australian bushmen refuse to speak the names of the dead, and this makes sense if you happen to believe, as these people do, that the ghosts might overhear and be angry. However, Anglo-American culture since Cromwell’s Puritan Revolution is unique in banning its entire native vocabulary of sexual terms, even refusing to list these words in dictionaries, as if to pretend that they do not exist. Thus an entire sexual vocabulary of ambiguous slang, cant, argot and Latinate euphemisms presently exists, officially unrecognized. (Of course, these words were originally omitted from the first dictionaries because they were too well known; early lexicographers only included rare or obscure words. But as dictionaries took on their modern form of complete references, these Words continued to be banned, and luck, for instance did not appear until the American Heritage Dictionary of 1969.)

That some psychological interpretation of this logophobia (fear of words) is necessary appears undeniable. It is 300 years since Bacon and Galileo, 100 years since Darwin. Men have walked on the moon; nobody (well, almost nobody) believes anymore that sticking a pin in a voodoo doll will kill a man. Why then do so many appear to believe that words and pictures pose some occult threat to society? Why are men still jailed for the “crime” of publishing over 200 years after the Peter Zenger case allegedly established freedom of the press on this continent? Why does the Supreme Court (except for that rare heretic, the late Justice Hugo Black) persist in believing, or claiming to believe, that the First Amendment does not mean what it says-namely, that no laws shall be established abridging freedom of speech or of the press?

Ralph Ginzburg entered Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary early in 1972, handcuffed to a bank robber and sentenced to a three-year term for the manner in which he promoted and advertised a magazine, Eros.Outcries against this are based mostly on reiterations of the simple and undeniable fact that Ginzburg, due to a series of legal mischances, went to jail for printing material far less controversial than much that had been published without prosecution in the ten years between his original trial and the time he went to prison. This certainly is worth emphasizing as an example of the irrationality of contemporary censorship, but it is even more worthwhile to ask why the devil a man was imprisoned at all for publishing erotica.

It has been asked, “If fuck is obscene, then is duck 75 percent obscene? Should it be printed as d—? The reader may feel superior to those who are even temporarily puzzled and disturbed by such a question, but what happens when the same kind of semantic (actually, symbolic) issue is moved to the visual arena? A photographer who exhibited 50 photos of flowers would certainly not be considered obscene; yet flowers are, as any high-school graduate knows after Botany WI, the genitalia of plants. Suppose the photographer held a show in which he exhibited 50 photographs of the genitalia of animals? Those who did not call him obscene would at least suggest that he was mentally unbalanced or had a very peculiar sense of humor. Only a passing acid-head might stop and say, “Wow, out of sight-beautiful, man!”

The case for censorship rests on two propositions: first, that sex is dangerous, and second, that even a symbolic representation of sex is dangerous. The censors, both public and private, believe that sex is dirty and threatening. Is that not paranoid?

It is time now-with the censors on the run-for all of us to come out of the shadows of shame and look at our language in the clear light of day.

For the reader’s convenience, all words used in definitions of other words, but which are themselves defined elsewhere, are set in small caps. They may be found in their own alphabetical sequence.